As we write this introduction to our latest article, the month of Ramadhan is currently underway, and many of us may be either observing Ramadhan or know people who are. So this week, we are extremely pleased and grateful to our NTU Psychology colleague, Rahmanara Chowdhury, for sharing reflections on the experience of Ramadhan; as a psychologist, and a Muslim, Rahmanara has a strong interest in learning about how we can share these experiences and build understanding between people and cultures. So Rahmanara’s article is about providing insight to those of us who may be less familiar, or would like to learn more about what it means to friends and colleagues who are engaging with it – both spiritually and practically.

I thought I would take this opportunity to share what it is like for someone observing Ramadhan with both a personal and psychology hat on, particularly in relation to the deeper significance of the month, and how students and staff observing Ramadhan might be impacted. I start with a disclaimer that I only represent myself within these reflections; my intentions are to share what my lived experiences are like when going through the month of Ramadhan on an annual basis in the hope that it might be useful when interacting with students and fellow colleagues. As most of my psychology work is grounded in building bridges, I would love for this article to be the start of an inter-faith conversation in which staff and students of all faiths, and none, can share their experiences too in our Departmental Blog. We also have a growing tradition of interest in the field of Spirituality, Religion and the Transpersonal and we have a Research Group in the School of Social Sciences that has been set up to create spaces for sharing knowledge and experiences within this realm. So, in sum, I am not intending this article to speak for the experiences of others; some of what I will share will be broad and general, and not necessarily applicable to all. Muslims come from all ethnicities and cultures so there is a lot of diversity in practice! For anyone who is not aware, Ramadhan is a month in which Muslims will engage in fasting (so no food or drink) from dawn to sunset, as well as many other things that I will go on to discuss. Fasting is also considered to be fasting of the person as a whole, so that means being aware of all the actions/speech one is engaging in and trying to leave those that are harmful.

Preparation for Ramadhan can begin well in advance of the month itself. Recommended actions are to practice fasting every Monday and Thursday, as well as on other significant occasions throughout the year, with this increasing towards Ramadhan but equally taking a break in the last few weeks so as to not wear oneself out. The start of the month can be the most difficult. For myself, this may involve withdrawal symptoms from not having my coffee, which leads to unpleasant headaches, as well as having to adjust physically to the new routine and less sleep. I do know people who wean themselves off caffeine before the month sets in but I’m afraid my willpower is not that strong! Fasting is to be done sensibly; it is not about making oneself suffer and become unwell, but to increase self-awareness, awareness of the Divine, and a contemplative mindset through abstention. It also allows one to get a closer understanding of what it is like for those who struggle to access food and water and thereby fosters empathy and the urge to carry out charitable acts for those in need. There are some extenuating circumstances which excuse individuals from fasting. This includes anyone who is ill, travelling on a non-normal journey, menstruating, pregnant, breastfeeding, has a medical condition, amongst others. Children also do not have to fast, although I recall thinking how cruel my parents were as I was growing up because they would not let me join in with everyone else when I was still too young to fast. I really wanted to be part of all the excitement. ‘Mini-fasts’ are therefore common as many children often want to feel part of the month and enjoy taking part in the iftar (breaking of the fast) regardless of whether they have fasted or not. This might involve fasting for a couple of hours, or half a day, depending on their age and ability, and may still entail having some food and water.

I have a good spring clean on the agenda for the weekend prior to the start of Ramadhan, I usually want to be able to start the month afresh, get rid of any clutter and bring out some lovely incense and oils I like to burn during the month. It is a time of intense awareness of the spiritual domain of life, and cleanliness and nice scents are part of this for me. These are also important elements of the Islamic tradition (if you ever go to a Muslim home, wear socks that you’re prepared to show off! It may be a no shoes policy!).

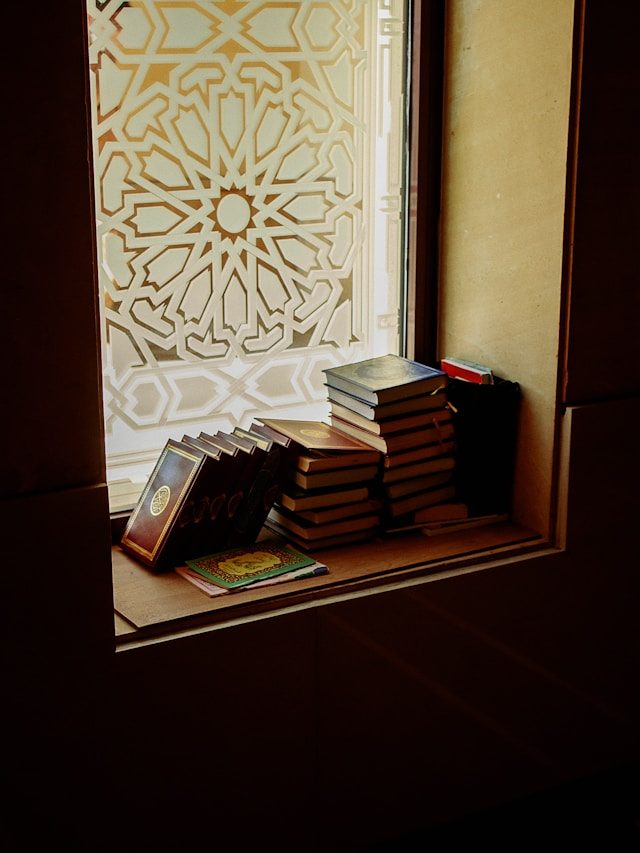

The significance behind Ramadhan is that it is the month in which the Qur’an was revealed. There are some details behind this, but I won’t go into that here, except to say that the Qur’an was revealed as the word of God to the prophet Muhammad[1], over a period of 23 years. The first approximately ten years of revelation focussed on teachings relating to knowing God, and understanding what it meant to have faith. Thereafter came various rules and regulations for existing as communities, once the Muslims migrated from the city of Makkah to the city of Madinah (in current day Saudi Arabia), due to the severe persecution they faced. Given the significance of the Qur’an, this month is therefore considered to be a sacred month, one in which those observing the month are required to take on a deeper level of introspection in relation to themselves, their past year and their future. Much of this introspection centres around God as the focal point, one’s relationship with God and how that shapes their everyday lives and personhood. It is therefore natural to find that people detach themselves from any unnecessary activities and spend more time in contemplation. Or it may be that they continue routines as normal (in some present day contexts this tends to be a non-option with work and study schedules) but do so whilst adopting a more contemplative mind-set.

A typical day in Ramadhan begins the night before! Every evening, extra prayers called Tarawih prayers are performed. These can be performed either at home or at the Mosque. Many opt for the mosque to get that communal feeling and to really absorb the Ramadhan spirit. This year these prayers will start around 7.30 p.m. and may end around 9 p.m. (variations exist across different mosques) and by the end of the month the entire Qur’an will have been recited within these prayers. As the clocks shift towards the end of the month these timings will begin later and therefore end later. Some individuals will wake up during the last part of the night, before dawn and engage in further additional prayers (known as Tahajjud), normally at home. This time in particular is highly significant for communicating with God, whilst everyone else sleeps, with Ramadhan being of extra spiritual significance in which to adopt this practice. This would normally be followed by a pre-dawn meal which most people will observe, which means waking up pretty early! I try to eat foods which will give me slow releasing energy throughout the day. This is followed by the first prayer of the day ‘Fajr’, which sets in just after dawn. Some may choose to engage in Qur’an recitation after their prayers, those who have a busy day ahead may try and get some more sleep before fully waking up for the day. It is a very small window though this year for extra sleep, so yawning tired Muslims may be more visible!

The rest of the day continues as normal, with the remainder of the daily prayers being performed at their respective times. Many will be keen to ensure they do not miss these, where through the rest of the year they may have been a little more flexible. Each prayer has a timeframe within which it can be performed. The most significant prayers during the work/study day are the second prayer (Dhuhr) and third prayer (Asr). Dhuhr is performed after high noon and into the early or latter part of the afternoon. The window for Asr is from this point until just prior to sunset. This is the most crucial time for staff and students to be able to get home so that they can get prepared to break their fast at sunset. Late meetings and late lectures therefore are not helpful as the fast must be broken on time, followed by performing the fourth set of prayers just after sunset (known as Maghrib). The timeframe for this prayer is much shorter than the other prayers; about 30 minutes, before the evening darkness sets in. People will also be hungry and will want to eat a proper meal after a day with no food or drink. Everyone tends to be involved in the breaking of the fast regardless of whether they are fasting or not, so it can end up being very communal and this is one of the celebrated aspects of Ramadhan (and what you will see on the media). However, it is the prayers and the increased deliberation on the bigger picture, purpose, and direction in my life which underpins the essence of Ramadhan for myself.

In light of this, my own personal practice is to keep my iftar meal quite simple and like a normal dinner at any other time of the year. If I am expecting guests for iftar however, I will make more of an effort! By the time the evening meal has been consumed it will be very close to the time for Tarawih prayers, alongside the final of the five daily prayers (known as ‘Isha). Many will rush to prepare for this, whether at home or at the Mosque, and may follow it up with further Qur’an recitation. The closest description I can get in terms of prayers is that it is an opportunity to cut off from the world and reground myself through meditative practices. This meditation however is not the same as other well-known meditative practices in psychology and well-being initiatives, as it involves direct communion with God through recitation of passages from the Qur’an. So, whilst you may have a room full of people praying at the same time, each and every person will in essence be engaged in their own personal dialogue and connection with God.

Hence, as you can see, there is very little time to do much else apart from devotional and contemplative actions during this month. That does not mean to say other work or study activities cannot take place, but that many will want to engage in the prayers and so aim to try and find a balance in their daily schedule to enable this. There may be a reluctance to take on extra projects or activities or non-urgent meetings. There may also be certain time points in the day when fatigue sets in and so breaks at those times are helpful. This can often be in the early afternoon. Or it may be that people prefer to sleep in and start their working day later, once adequately rested. I know this certainly helps me. Equally some actively seek out extra activities, for example University Islamic societies may hold extra activities, this would form part of their Ramadhan experience and charitable acts.

Ramadhan is also a time for engaging is as much pro-social behaviour as one possibly can, as part of the whole spiritual cleansing of the month and particularly as good deeds are considered to draw extra rewards during Ramadhan. Therefore, there will be lots of money being raised for charities across the world, alongside numerous other charitable initiatives. The Muslim Charities forum estimate that UK Muslims have previously donated more than £130 million during this month[2]. Beyond this, one thing I ensure to do in Ramadhan is to pay my zakat. Zakat is where a person must give 2.5% on any surplus wealth they hold that year, if they have held a minimal threshold amount for the duration of that year. This is then distributed to those who do not possess this minimum amount of wealth and are in need. It is viewed as a religious duty that also acts as a form of purifying one’s wealth, so that one does not become complacent of their duty to care for others who do not have the same opportunities or access to provision in society.

It’s important to remember that many people might struggle with Ramadhan for different reasons. People with eating disorders or gastrointestinal syndromes may encounter problems in keeping up with their fast over the month and so the significance of breaking the fast and the overwhelming presence of food can make this a difficult time. Busy parents who are trying to manage work alongside children and/or family obligations may be more stressed during this month. Individuals may have negative associations with the month for other reasons. Perhaps they are isolated from family and so have no or limited social connections for what might have otherwise been an incredibly social time for them. This may be particularly true of the student population or staff who are away from family and community. It may be useful to know that many University Islamic societies will often serve dates and water and perhaps an iftar meal in the campus prayer room (or a designated space). Anyone is welcome, whether fasting or not, and indeed whether Muslim or not.

I hope this small insight might be of some use to those who read this article. My final reflections: Ramadhan is a deeply meaningful time for me but if you happen to pass me by with your lunch or a coffee, you will not offend me, so please don’t worry. I want to be part of this month and it helps me reground myself each year. Some years are admittedly better than others, but that is part of my spiritual journey.

About Dr. Rahmanara Chowdhury

Rahmanara is a Senior Lecturer at Nottingham Trent University, primarily interested in domestic violence and abuse, spiritual abuse, forensic mental health, intersectionality, decolonial approaches to forensic research, and holistic approaches to wellbeing. Her research often intersects with all of these.

[1] Peace be upon him (as per the etiquette of the Muslim tradition)

[2] https://www.gov.uk/government/news/commission-urges-public-to-give-safely-during-ramadan

- If you’d like to learn more about everyday experiences of Ramadhan, you can find further personal reflections via this podcast series: Muslim Women Talk Ramadan / Week 2 (Nadiya Hussain) (audioboom.com)

Image credits

- Header image: Photo by Saj Shafique on Unsplash

- Image 1: Photo by Malik Shibly on Unsplash

- Image 2: Photo by Rahmanara Chowdhury

- Image 3: Photo by Masjid Pogung Dalangan on Unsplash

- Image 4: Photo by Rahmanara Chowdhury