This article sets out to explain the inextricable link between family relationships and experiencing clinical and sub-clinical levels of schizophrenia. It also explains how family intervention can help families to become more competent in understanding their relative’s distress. Having positive family relationships is important for experiencing good mental health. Feeling accepted and supported, but also having autonomy within the family are some of the ways in which families can promote mental health (Olson, 2011).

Mental health is defined as, ‘A state of well-being that enables the individual to realise his or her potential, cope with stressors in the environment and contribute to his or her society’, and ‘An individual ability as humans to think, emote, interact with each other, earn a living and enjoy life’ (World Health Organisation, 2018).

Schizophrenia is a debilitating mental disorder. A person with schizophrenia hears voices, has false beliefs of grandeur, or is paranoid – that is convinced beyond reason – that people are trying to harm them. A person diagnosed with schizophrenia may experience emotional withdrawal, odd speech and worrying. On the one hand, it is easy for the family to become estranged from their relative’s experience of psychotic symptoms. On the other hand, the family can be excessively concerned over the welfare of their relative. Caring for a person who has schizophrenia can be burdensome, especially if the family feels hopeless about the mental and social outcomes of the patient’s illness or is nostalgic for the way the patient was before they became ill (Onwumere, Shiers, & Chew-Graham, 2016; Onwumere, et al., 2009). It has long been recognised that such disruptive family dynamics perpetuate schizophrenia. Laing and Easterson (1970) chronicled the family histories of eleven people with schizophrenia and noted the odd family dynamics, such as disorganised speech, in these families.

Brown and colleagues (Brown, Monck, Carstairs, & Wing, 1962; Brown, Birley, & Wing, 1972) conducted the Maudsley Family studies. Brown and colleagues (1962/1972) systematically investigated the family dynamics of patients with schizophrenia who were discharged from hospital in London. Brown, Monck, Carstairs and Wing (1962) found that 52% of 128 patients deteriorated after recovering and being discharged from hospital. Among the patients who deteriorated, 76% deteriorated if their family had high emotional concern. From these investigations grew the Theory of Expressed Emotion (Leff & Vaughn, 1985). The Theory of Expressed Emotion (EE) states that a patient with mental disorder is likely to deteriorate if their family expresses an excessive amount of criticism, hostility, emotional over-involvement, warmth and positive comments towards the patient. EE refers to this collection of emotions that a family member expresses towards a person who is diagnosed with a mental disorder. High EE increases the likelihood of relapse of schizophrenia (Bebbington & Kuipers, 1994). High EE also increases the likelihood of conflictual communication between the family and the patient (Rosenfarb, Goldstein, Mintz, & Nuechterlein, 1995). Patients are more likely to display anxious or agitated behaviors and hostile or unusual behaviors (Woo, Goldstein, & Nuechterlein, 2004) and experience anxiety and depression subsequently when they encounter high EE (Kuipers, et al., 2006).

Expressed emotion and schizotypy

High EE precedes the onset of schizophrenia (Meneghelli, et al., 2011). Schizotypy is a personality organisation that reflects psychosis-like experiences at a sub-clinical level. Schizotypy denotes a putative liability for schizophrenia (Fonseca-Pedrero, et al., 2018; Grant, Green, & Mason, 2018). Schizotypy is a multidimensional construct. One of the three schizotypal dimensions is positive schizotypal traits, such as believing in the paranormal. Negative schizotypal traits, such as lacking enjoyment in social and physical activities, and disorganisation, such as having poor concentration and social anxiety, are other schizotypal traits. People with high schizotypal traits encounter high EE (Premkumar, et al., 2013). We examined the effect of EE on the brain by asking relatives of participants with high schizotypal traits and relatives of participants with low schizotypal traits to audio-record themselves relaying criticism and praise (Premkumar, et al., 2013). People with high schizotypal traits fail to activate the brain regions associated with reward and attaching importance to events when they listen to praise from their relative (Premkumar, et al., 2013). This finding suggests that people with high schizotypal traits do not find praise as rewarding as people with a low level of schizotypy traits. Other evidence suggests that people with high schizotypal fail to activate the brain centres for feeling the pain of rejection when looking at pictures depicting social rejection (Premkumar, et al., 2012). This finding suggests that people with a high level of schizotypal traits become resilient to the pain of rejection.

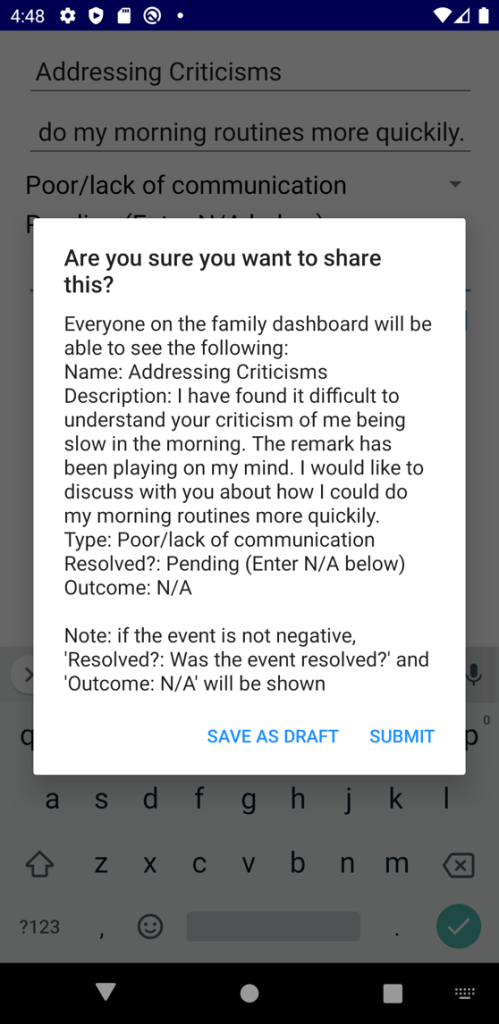

Criticism is a key component of EE that influences the outcome of patients with schizophrenia (Onwumere, et al., 2009). We have developed a listening task for evaluating sensitivity to criticism and praise in family communication (Premkumar, et al., 2019). The listening task consists of criticisms, such as ‘I can’t stand it when you are late; you leave things till the last minute and panic when it’s too late’, and praises, such as ‘You have a very special way of treating people because of your sensitive nature. It makes me proud of you’. We asked ninety-eight healthy participants to listen to these criticisms and praises and rate how personally relevant the comments were for them. People are more likely to find the criticism personally relevant if they have a high level of positive schizotypy traits, such as believing in paranormal activities and hearing voices (Premkumar, et al., 2019). People are more likely to find the criticism personally relevant if they have a high level of disorganisation due to having poor concentration and perceiving threat from others (Premkumar, et al., 2019). The relationship between schizotypy and finding criticism personally relevant is particularly strong if people feel depressed and consider their family irritable. Depression consists of having negative automatic thoughts, such as being self-critical. Hence, depression and finding the family irritable can mediate the relationship between perceiving criticism and schizotypy.

Family intervention

Dr Preethi Premkumar is a neuroscientist. Her expertise lies in family relationships and social anxiety, and their relationship to vulnerability for schizophrenia.

Header image credit: National Cancer Institute on Unsplash

References

Bebbington, P., & Kuipers, E. (1994). The predictive utility of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: an aggregate analysis. Psychological Medicine, 24, 707-718.

Bird, V., Premkumar, P., Kendall, T., Whittington, C., Mitchell, J., & Kuipers, E. (2010). Early intervention services, cognitive-behavioural therapy and family intervention in early psychosis: Systematic review. British Journal of Psychiatry, 197(5), 350-356.

Brown, G. W., Birley, J. L., & Wing, J. K. (1972). Influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic disorders: a replication. British Journal of Psychiatry, 121(562), 241–258.

Brown, G., Monck, E., Carstairs, G., & Wing, J. (1962). The influence of family life on the course of schizophrenic illness. British Journal of Preventive and Social Medicine, 16(2), 55-68.

Fonseca-Pedrero, E., Debbané, F., Ortuño-Sierra, J., Chan, R. C., Cicero, D. C., Zhang, L. C., . . . Jablensky, A. (2018). The structure of schizotypal personality traits: A cross-national study. . Psychological Medicine, 48, 451-462.

Grant, P., Green, M. J., & Mason, O. J. (2018). Models of Schizotypy: The Importance of Conceptual Clarity. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 44(2), S556–S563.

Kuipers, E., Bebbington, P., Dunn, G., Fowler, D., Freeman, D., Watson, P., & Garety, P. (2006). Influence of carer expressed emotion and affect on relapse in non-affective psychosis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 188, 173-179.

Laing, R. D., & Esterson, A. (1970). Sanity, madness and the family: families of schizophrenics. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Leff, J., & Vaughn, C. E. (1985). The Expressed Emotion Scales. In J. Leff, C. E. Vaughn, J. Leff, & C. E. Vaughn (Eds.), Expressed emotion in families: Its significance for mental illness (pp. 37-63). London: Guidlford Press.

Ma, C. F., Chien, W. T., & Bressington, D. T. (2018). Family Intervention for carers of people with recent-onset psychosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 12, 535-560.

Meneghelli, A., Alpi, A., Pafumi, N., Patelli, G., Preti, A., & Cocchi, A. (2011). Expressed emotion in first-episode schizophrenia and in ultra high-risk patients: Results from the Programma2000 (Milan, Italy). Psychiatry Research, 189(3), 331–338.

Olson, D. (2011). FACES IV and the Circumplex Model: Validation Study. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 37(1), 64-80.

Onwumere, J., Kuipers, E., Bebbington, P., Dunn, G., Freeman, D., Fowler, D., & Garety, P. (2009). Patient perceptions of caregiver criticism in psychosis: links with patient and caregiver functioning. . Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 197(2), 85-91.

Onwumere, S., Shiers, D., & Chew-Graham, C. (2016). Understanding the needs of carers of people with psychosis in primary care. BritishJournalofGeneralPractice, 66(649), 400-401.

Premkumar, P., Dunn, A., Kumari, V., Onwumere, J., & Kuipers, E. (n.d.). A Behavioural Task to Measure Appraisal of Standard Criticism and Standard Praise. Personal communication.

Premkumar, P., Ettinger, U., Inchley-Mort, S., Sumich, A., Williams, S., Kuipers, E., & Kumari, V. (2012). Neural processing of social rejection: The role of schizotypal personality traits. Human Brain Mapping, 16(8), 587-601.

Premkumar, P., Williams, S. C., Lythgoe, D., Andrew, C., Kuipers, E., & Kumari, V. (2013). Neural processing of criticism and positive comments from relatives in individuals with schizotypal personality traits. , 14,. World Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 14, 57-70.

Rosenfarb, I., Goldstein, M., Mintz, J., & Nuechterlein, K. (1995). Expressed emotion and subclinical psychopathology observable within the transactions between schizophrenic patients and their family members. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 104(2), 259–267.

Woo, S. M., Goldstein, M. J., & Nuechterlein, K. H. (2004). Relatives’ affective style and the expression of subclinical psychopathology in patients with schizophrenia. Family Process, 43(2), 233–247.

World Health Organisation. (2018, March). https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-strengthening-our-response.