By Rob Hutton, Psychology Lecturer

This week, Rob Hutton gives an insight into some of the challenges of applying psychology in practice, showing that psychology isn’t only about roles with ‘psychologist’ in the title. You’ll also notice that the contacts and networks he has built up over years of experience can lead to exciting projects.

Last year I was approached by two organisations, out of the blue, for advice and support. One ended up being two days of consultancy including a professional development workshop on incident analysis and the other ended up with a short two-hour leadership development session about metacognition and developing decision making skills.

The first approach was by the UK’s only independent investigator of patient safety concerns in NHS-funded care across England: the Healthcare Safety Investigation Branch (HSIB). I had worked with them briefly a few years ago on an incident investigation and as a result I delivered a half-day workshop focused on field research methods for understanding the cognitive aspects of performance in medical contexts. Investigating cognition ‘in the wild’ can be a real challenge and relates to two key considerations: 1) cognition is unobservable; 2) cognition is really hard for people to describe, especially for skilled/expert personnel. This means that when investigating incidents or issues relating to cognition (e.g. an incident related to mis-administration of a drug) investigators cannot directly observe the cognitive issues directly, and they cannot ‘just ask’ the healthcare practitioners about what they were thinking at the time. The cognitive task analysis (CTA) workshop I delivered provided the HSIB with some background theory/models of decision making and other aspects of cognitive performance so that they knew what the targets of the CTA methods were. The purpose of the workshop was to add to the investigative analysis toolkit to understand (cognitive) work in the healthcare environment. It also provided some interview methods focused on critical decision incidents and also aspects of expert performance with respect to cognitive work (i.e. what do expert performers do when they make difficult assessments or decisions?).

The second approach was through someone who had found me via some work I had done with University of Bath Executive MBA programme. It turned out that the World Health Organisation (WHO) was currently improving their Health Emergency Leadership Development programme for their healthcare emergency managers all over the world. They wanted to have a session focused on developing decision-making skills and we covered rational and intuitive decision making, decision making environments with differing degrees of structure, stability and predictability. Most importantly we looked at ways, as leaders and managers, of being more aware of our own decision-making strengths and limitations, and how to improve them based on structured learning from experience activities such as a decision-centred After Action Review. Because decision making (and the related cognitive activities) are hard to articulate and hard to assess, we often find that developing and improving decision making is left to chance, rather than providing structured learning and development activities to develop better decision making. In addition, when decision-making has been trained in the past, the training is based on how we think people should make decisions, rather than recognising how they actually make decisions, and why decision making is challenging in the operational context. The leadership development sessions focus on how to improve decision making skills by targeting decision making with specific activities that support learning from experience and developing expert, skilled performance.

Both of these efforts have follow-on activities; I am currently supporting the HSIB with an ongoing study of aspects of diagnosing hard-to-diagnose conditions in emergency medicine, and the WHO is hoping to expand the reach of its leadership programme and will include more sessions exploring processes for decision making in health emergencies and how to improve leader decision making skills.

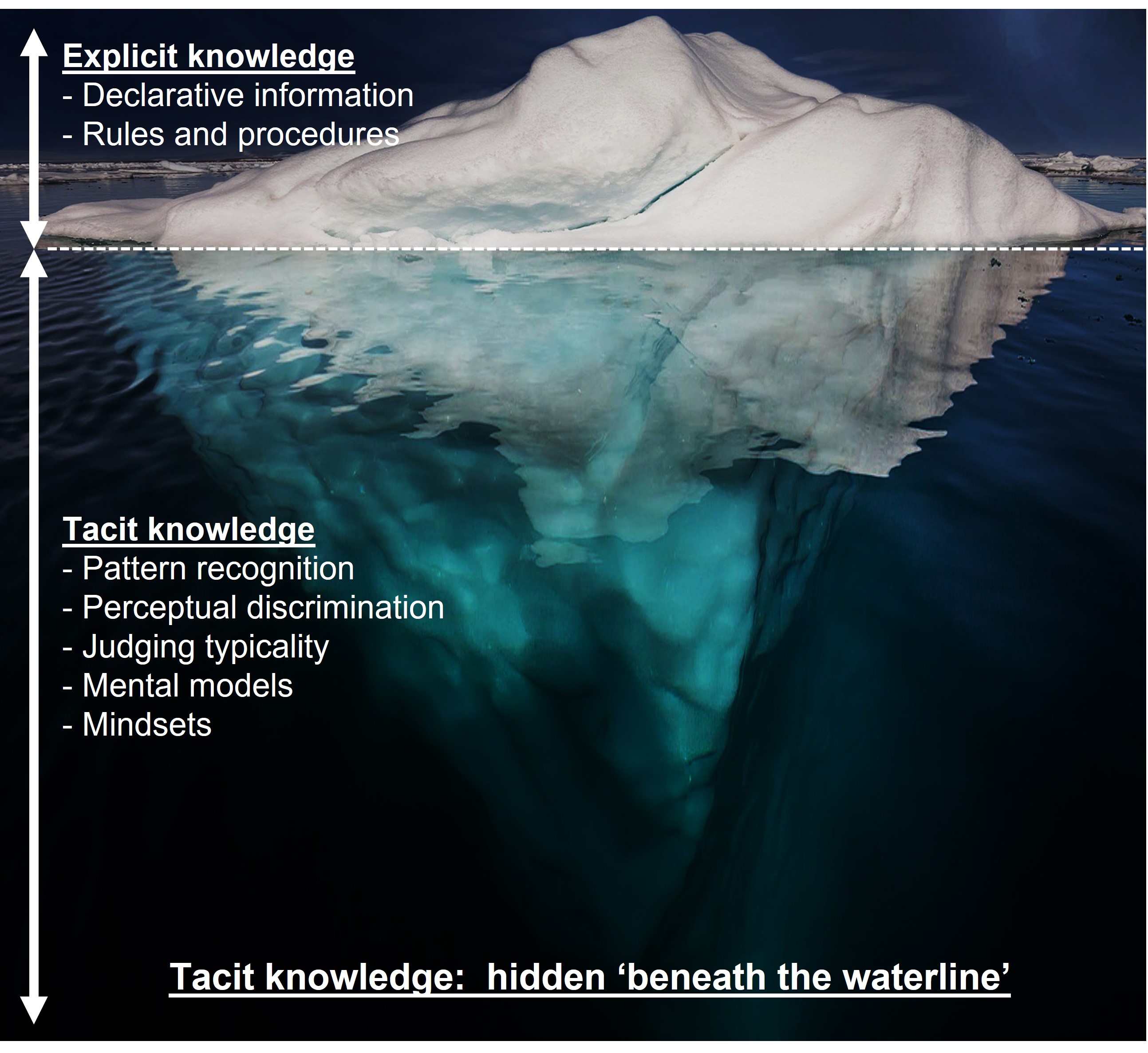

With respect to cognitive psychology, there is one common theme to these opportunities; both are about understanding the nature of cognitive work. One of the key challenges to identifying and exploiting an understanding of cognitive work is the nature of tacit knowledge. Tacit knowledge is the knowledge that experienced people have as a result of their experience and the encoding of knowledge and skills to the point of no longer being able to access it explicitly – when you’re that skilled at something you just ‘do’ it. This could be as a result of implicit learning (e.g. Berry & Broadbent, 1987) or automaticity (e.g. Schneider & Shiffrin, 1977).

Image: adapted from AWeith/ CCBY4.0

Gary Klein (2018) discusses the identification and exploitation of tacit knowledge in the development of expertise and skilled performance: “…expertise depends on tacit knowledge rather than explicit knowledge of facts, rules, and procedures. By tacit knowledge, I mean the perceptual skills required to make fine discriminations, to detect patterns, to judge familiarity (and therefore to notice anomalies), to draw on a rich mental model of causal relations. These are the items under the waterline in the diagram [above].” Tacit knowledge is critical to understanding how cognitive work is accomplished. CTA methods are intended to support the mining of tacti knowledge as a valuable resource for individual and organisational learning.

About Rob

Rob is a lecturer in psychology at NTU. He has worked at the intersection of research and applications in the area of the psychology of cognitive work for over 25 years. His work has looked at how to improve cognitive work performance in complex human-technology organisations and implications for the design of technology, training and work processes. This has included the development and elaboration of theory, methods, and measurement of cognitive work and processes and guidance for incorporating human factors into the design process. He is a Fellow of the Chartered Institute of Ergonomics and Human Factors (https://www.ergonomics.org.uk).

References

Berry, D.C., & Broadbent, D.E. (1987). The combination of explicit and implicit learning processes in task control. Psychological Research 49, 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00309197

Klein, G. (2018, November 6). Getting smarter: Nine tips for gaining expertise. Psychology Today: Seeing What Others Don’t. https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/seeing-what-others-dont/201811/getting-smarter. Retreived, April 2021.

Schneider, W., & Shiffrin, R. M. (1977). Controlled and automatic human information processing: I. Detection, search, and attention. Psychological Review, 84(1), 1.