by Preethi Premkumar, Nadja Heym, Alexander Sumich

This week, Preethi Premkumar, Nadja Heym, and Alexander Sumich share some of their latest research, which provides some reassurance for those of us who experience one of the most common social phobias: fear of public-speaking. It’s something that all students will have to face during their studies, so this work on how Virtual Reality can be used to ease those fears and improve public-speaking skills in a safe environment is great news…

And if you are interested in contributing to the team’s latest exciting research into the applications of Virtual Reality, you can find details at the end of this post or follow this link to go straight to the research study information page.

Social anxiety can be experienced when meeting other people, typically out of fear of being negatively evaluated, criticised, rejected or embarrassed. However, sometimes we can also feel anxious around being praised. Such social anxieties are even more prominent in people with certain personality traits, such as schizotypy (Premkumar et al., 2020; 2019; 2018) – a personality style involving unusual beliefs and experiences, susceptibility to suspicion (Sumich et al, 2014), and introversion, that sometimes co-occurs with addictive behaviours (Wang et al., 2021). Social anxiety disorder occurs when these fears of interacting with people have a devastating impact on the daily functioning of the person and the fear of being evaluated by others is highly exaggerated. Social anxiety is the third most common psychiatric disorder (Kessler et al., 2005), and can seriously affect personal relationships, the ability to form a therapeutic alliance with a therapist, engagement in work and education.

Public-speaking anxiety is a form of social anxiety where the person fears performance situations, such as speaking in front of an audience. The person is apprehensive before delivering a speech, which may affect their speech, causing loss of train of thought, pauses and stuttering. Students regularly find themselves preparing for and delivering a public speech. Public-speaking is also a common mode of communication in employment settings. While it seems that these fears can be overcome by repeated exposure, many students dread the thought of having to face a large audience, especially when they are aware that their performance is being evaluated. Exposure therapy is a widely accepted and effective psychological intervention for social anxiety, especially public-speaking anxiety (Powers, Sigmarsson & Emmelkamp, 2008). The person is encouraged to be exposed repeatedly to feared social situations and modify their thoughts and beliefs around those situations.

Virtual-reality exposure therapy (VRET) has become a popular mode of psychological intervention in helping people modify their fears. The advent of virtual-reality technology in the gaming industry has seen the rise in the popularity of VRET. Self-guided VRET represents the latest advance in virtual-reality therapy (Lindner, 2020) whereby the individual controls their own gradual exposure to virtual threats without risking over-exposure to those. Self-guided VRET can also help in situations in which the individual dreads a face-to-face encounter with a therapist. Even a single session of self-guided VRET for social anxiety disorder can produce large improvements in public-speaking anxiety (Lindner et al., 2019; Premkumar et al., 2021).

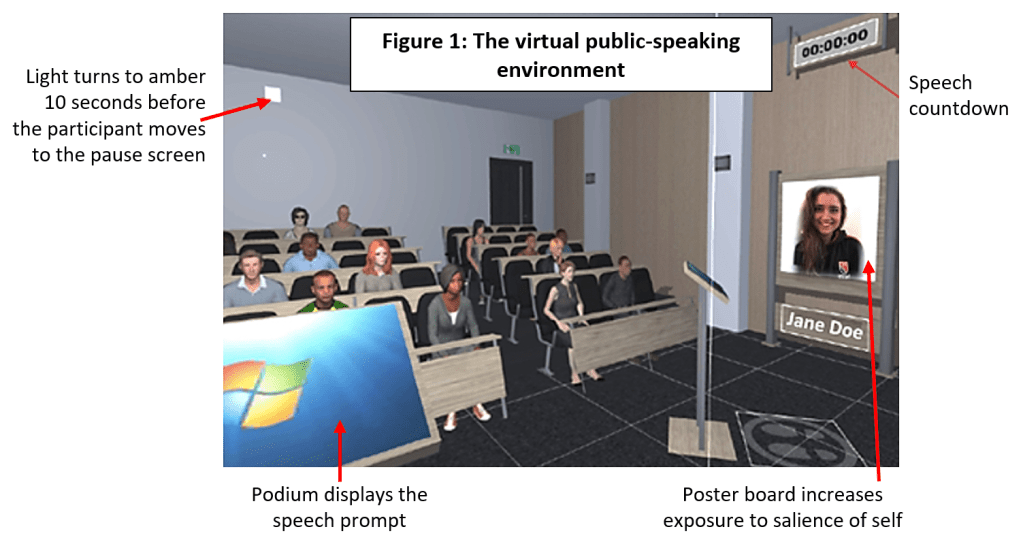

Expert psychologists and computer scientists at Nottingham Trent University, London South Bank University and University of British Columbia in Canada have developed a virtual-reality exposure therapy (VRET) that aims to improve public speaking anxiety (Premkumar et al., 2021). The self-guided VRET comprises an immersive virtual-reality three-dimensional environment designed with the intention of creating three levels of exposure to social threat (low, medium and high). There are five kinds of virtual social threat to which participants could increase exposure (Figure 1, below), namely:

- Audience size (small, medium and large),

- Audience reaction (positive, neutral and negative),

- Distance from the audience (home, close and closest),

- Quantity of speech prompts on a PowerPoint presentation that appeared on the podium in the virtual environment (many, few and fewest), and

- Salience of self as speaker. A high level of salience of self as speaker meant that the participant could see a picture of themselves in the virtual environment, since seeing oneself in the virtual environment is found to be anxiety-provoking (Aymerich-Franch, Kizilcec & Bailenson, 2014).

Thirty-two psychology students from Nottingham Trent University with high public-speaking anxiety took part in the VRET study for public-speaking anxiety. Sixteen percent of the sample had a previous or current diagnosis of social anxiety disorder. The self-guided VRET was delivered with a Samsung Gear VRInnovator Edition headset. Participants gave a 20-minute speech in each self-guided VRET session and two self-guided VRET sessions were delivered one week apart. Participants were taken into a pause screen after every four minutes so that they could modify the virtual environment and change their exposure to the elements of virtual social threat. They also rated their avoidance, anxiety and arousal at these intervals. Participants also assessed their public-speaking anxiety on self-report questions after each session and one month later. Our findings supported our hypotheses, such that:

- Self-guided VRET encouraged individuals to voluntarily and gradually increase their exposure to virtual social threat;

- Reductions in self-reported anxiety concomitantly reduced physiological arousal (e.g., heart rate) throughout the ongoing self-guided desensitization to virtual social threat, and…;

- Self-guided VRET significantly improved public-speaking anxiety immediately after intervention and at 1-month follow-up.

Currently, the research team is continuing to further develop and test this self-guided VRET. The second phase sees us examining the role of biofeedback in supporting self-guided VRET. Receiving biofeedback about one’s heartrate improves control over threatening thoughts (Clamor, Koenig, Thayer & Lincoln, 2016); however, at the same time there is concern that it might distract and deteriorate performance. Thus, we tested whether paying attention to biofeedback in the self-guided VRET would limit performance and improvements in social anxiety. We tested this in 50 highly socially anxious people from the general public. Preliminary analysis of the data suggests that receiving biofeedback about one’s level of arousal does not differ from receiving no biofeedback in reducing public-speaking anxiety. This suggests that proper biofeedback training protocols may be integrated into the VRET without adversely affecting users. For this guidance will be provided about what the biofeedback means and how to decrease anxiety based on the feedback using certain strategies. Users may learn to become aware and modulate their physiological arousal to reduce their anxiety levels. VRET continues to offer great promise in addressing threat gained from maladaptive fear conditioning.

Would you like the opportunity to contribute to the team’s latest VR research? Here’s how you do it, and what it involves 👇

A team of psychology researchers are conducting a research study to investigate the effectiveness of a virtual therapy, Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy (VRET), in reducing social anxiety.

We understand that people with social anxiety may fear being criticised, scrutinised, or embarrassed when they are with others, particularly when public speaking. This research study aims to (i) measure people’s level of social anxiety when speaking in front of a virtual audience, and (ii) assess whether increasing one’s exposure to a virtual audience whilst giving a speech gradually reduces their social anxiety.

We have previously shown that our VRET was successful in reducing anxiety when university students gave a public speech. We are now expanding our investigation to those in the general public who experience social anxiety.

We are seeking people over 18 years who experience social anxiety (e.g., fear of speaking in front of others, fear people will judge you). They must also have normal or corrected vision with contact lenses), so that they can see the virtual environment clearly, and no history of neurological disorders (e.g., epilepsy).

There are three stages to the study (part 2 is by invitation only):

– Stage One: Completion of the an online survey (approx. 20 mins) about fear of social situations: click here for more information and to participate in this first stage.

– Stage Two: If invited, participants will take part in three VRET interventions, involving a 20-minute talk in front of a virtual audience on a familiar topic (presentation content/slides will be provided). We will also measure your heart and brain responses during this. If you are interested, more information will be provided before signing up.

– Stage Three: Participants who took part in stage 2 will be invited to complete a brief online survey at approximately 1 month following their participation.

ALL who take part in stage 1 (online survey) can opt to be entered into prize draw for a £10 Love-to-Shop gift voucher. For stage 2, you will receive a £10 Love-to-Shop gift voucher following each of the 3 intervention sessions (£30 in total). And For stage 3, you will be entered into a prize draw for one of 5x £10 Love-to-Shop gift vouchers when you complete the brief follow-up survey after the virtual reality sessions.

For more information: please do not hesitate to contact the team (nadja.heym@ntu.ac.uk, ina.kaleva@ntu.ac.uk, or phoebe.formby@ntu.ac.uk) who will be happy to give more details about the study.

References and further reading…

- This research has also been featured in an article, “Virtual Reality Making Progress as Depression Treatment“, which has been among the top 25% of all research outputs since its publication on Medscape.

- Aymerich-Franch, L., Kizilcec, R. F., Bailenson, J. N. (2014). The relationship between virtual self-similarity and social anxiety. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 8, 944. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00944

- Clamor, A., Koenig, J., Thayer, J. F., Lincoln, T. M. (2016). A randomized-controlled trial of heart rate variability biofeedback for psychotic symptoms. Behavior Research and Therapy, 87, 207–215. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2016. 10.003

- Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 62, 593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593

- Lindner P, Miloff A, Fagernäs S, Andersen J, Sigeman M, Andersson G, et al. (2019). Therapist-led and self-led one-session virtual reality exposure therapy for public speaking anxiety with consumer hardware and software: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 61, 45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.07.003

- Lindner P. (2020). Better, virtually: the past, present, and future of virtual reality cognitive behavior therapy. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 14, 23–46. doi: 10.1007/s41811-020-00090-7

- Powers, M. B., Sigmarsson, S. R., & Emmelkamp, P. M. G. (2008). A meta–analytic review of psychological treatments for social anxiety disorder. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 1(2), 9- 4–113.

- Premkumar, P., Alahakoon, P., Smith, M., Kumari, V., Babu, D., Baker, J. (2020). Mild-to-moderate schizotypal traits relate to physiological arousal from social stress. Stress, 24 (3), 303-317.

- Premkumar, P., Heym, N., Brown, D. J., Battersby, S., Sumich, A., Huntington, B., Daly, R., Zysk, E. (2021). The Effectiveness of Self-Guided Virtual-Reality Exposure Therapy for Public-Speaking Anxiety. Frontier in Psychiatry, 12, 694610. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.694610

- Premkumar, P., Onwumere, J., Betts, L., Kibowski, F., & Kuipers, E. (2018). Schizotypal traits and their relation to rejection sensitivity in the general population: Their mediation by quality of life, agreeableness and neuroticism. Psychiatry Research, 267, 201-209.

- Premkumar, P., Santo, M. G. E., Onwumere, O., Schürmann, M., Kumari, V., Blanco, S., Baker, J., Kuipers, E. (2019). Neural responses to criticism and praise vary with schizotypy and perceived emotional support. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 145, 109-118.

- Wang, G. Y., Premkumar, P., Lee, C. Q., Griffiths, M. D. (in press). The Role of Criticism in Expressed Emotion Among Psychoactive Substance Users: an Experimental Vignette Study. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction.

Images:

- Header photo by Kane Reinholdtsen on Unsplash

- Presenter and audience photo by William Moreland on Unsplash

- ‘You got this’ photo by Prateek Katyal on Unsplash